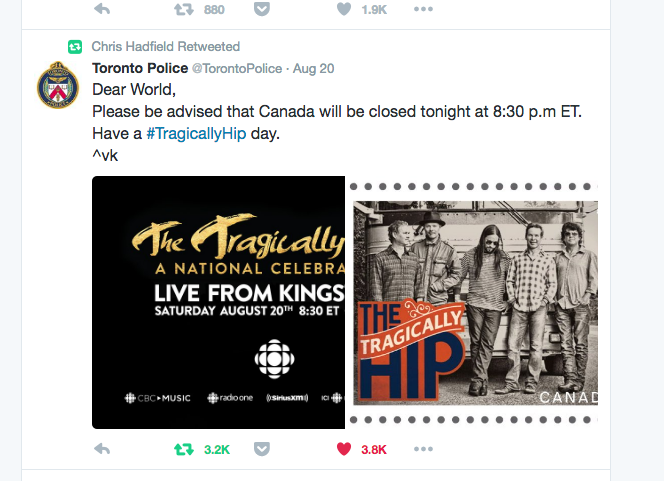

screencapped from twitter.

[Originally posted to dreamwidth in May, 2017]

I went to two shows on the Tragically Hip's Man Machine Poem Tour in the summer of 2016. I've been to a hundred different shows by a hundred different artists: profound, profane, good, bad and ugly. This tour was different, because it held the heartbeat of our nation cradled in the palm of its hand.

Originally I finished a draft of this piece in early September, 2016, and put it away until it hurt a little less. Spoilers: it doesn't hurt any less. Grief is like that.

screencapped from twitter.

I'm already starting to forget The Hip In Kingston.

It seems unimaginable.

How could I manage to blur that most profound of concerts into memory, into a smudged glass? This morning I watched someone else's compilation of their photos -- someone's brother was in the crowd that night, taking photographs, memorializing all the tee-shirts and the tears and the small moments that happen when you get twenty thousand people singing outside the arena.

Twenty thousand people outside. Only sixty-seven hundred inside.

So I was there, in the K-Rock arena in Kingston, for the last show the Hip played this tour. I went with a friend. As they put it, "one of my oldest friends", not one of my closest. Not anymore.

(I warn you now, this is full of nostalgia and a little bit of misery. But then, it's a wake, a greek tragedy, a rock show, all in one; it seems fitting.)

The truth is, no concert is perfect. Nothing is perfect except in the way we remember it. Trying to recreate in words What Happened In Kingston, I'll forget how I got distracted while they played Fifty Mission Cap and stared out at the crowd. I'll forget how irritating the guy beside me was, drunk and leaning (I didn't drink; I don't need to drink to feel sorrow, so it seemed a bad idea). But already, those imperfections have been gaussian-blurred over, a softer filter. "I was there," I can say, "and so it was everything I imagined it to be."

Of course it wasn't, not really. But now it is.

Confession time: my masters' project involved experiential research into fan interaction at concerts, my own fumbling devotion to storytelling and shows and arenas and stadiums and clubs chanting lyrics together. A large portion of it was awkward and uncomfortable. Who wants to look inside their own embarrassment, admit they've gone past where they should, into Being A Fan?

The show that got me started on my research was a MuchMusic special, broadcast live, and the crowds were on camera just as much as the band. I remember being very uncomfortable any time the camera people came near us, all three of us hiding our faces, turning away -- even though I'd waited in line, in the rain, for four hours to get the wristbands that would allow us entry to the crowd.

We waited hours to get in, but didn't want to admit it.

I ducked from all cameras, face hidden, turned away from the lens. Maybe it's just because I spent so much time researching people whose eyes function as lenses -- fans who stare, who watch, who use their gaze to create spaces. Maybe it's just because I don't like the idea of recording moments in time.

If I want to remember What Happened In Kingston, now, I have to rely on other people's cameras, other people's digital memories. I have maybe two-dozen photos, quick phone snapshots of a concert crowd that could have been any show, any time, any venue. Those pictures only contain meaning because I know they contain meaning, know where they are. Just like that first show at MuchMusic, I was one of the few to be behind the camera, to have the show un-obscured by someone else's camera...but only in that moment.

Now, my memories are muddy, just like yours. But for a few hours, That Night In Kingston, I watched Gord cry myself, not through the television set. It's always meant something to me, being able to see without the glass in between, and I will never regret having been in the arena, instead of outside; even if there were only six thousand people to share it with, instead of the entire country.

Because sitting in that seat, in the back of K-Rock, watching the CBC boom-camera swing around? We could feel the country watching, too. And that is something else.

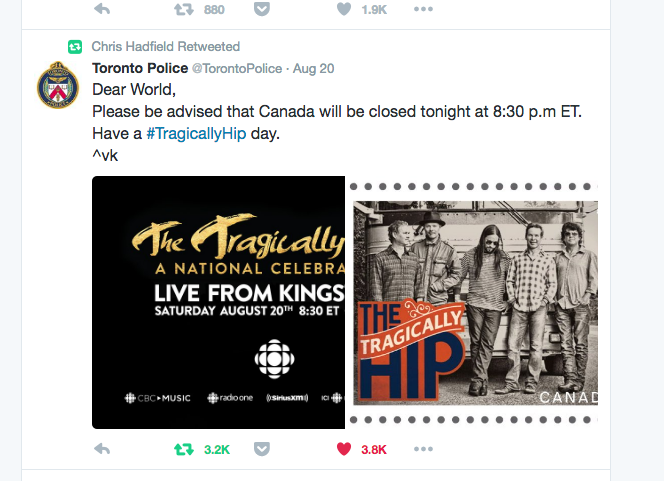

setlist, july 30

"It has left a vapour trail of heartbreak and exhilaration, this act of enormity." --Marsha Lederman

I need to back up a few steps. The first show I went to on this tour was actually in Edmonton.

I live and breathe Toronto, but tickets were impossible to get, and I was flying from the arctic. I would be trekking from the forgotten north wherever I ended up getting tickets, so when I failed on all the Ontario shows and Edmonton released more, I snapped a pair up. It wasn't Toronto, but I told myself it was better than not getting to go.

A friend and I flew down for the weekend. We walked, and drank, and talked a lot about the perfect day, the perfect memory. Through some alchemy of luck and weather and planning, we had that perfect day.

The day before we flew down, everyone was talking about the tour. People in Yellowknife happily fly to Edmonton for concerts all the time -- several people we knew were in the audience that night, too. At work, in an office full of lawyers of all ages and backgrounds, we were still talking about what our favourite Hip songs were.

I can't remember who I said it to, but my immediate reaction was, "I can't possibly pick. There's no way." I automatically followed up with, "well, but, gun to my head, Wheat Kings".

So we got to the stadium, we got inside. The Hip started playing.

The internet tells me it was right before the second break that they played Wheat Kings, and I remember weeping about halfway through. Not because the song makes me cry -- although it does, god, it does. I wept, because I had the distinct thought, "I may never get another chance to hear this song live."

But I got lucky twice, and they also played it in Kingston.

The second time, even though it was the same song and I still wept, it was different.

It felt like a real historic moment -- the kind you can't help but craft, and yet the kind that dies when scripted. Because in Kingston, only three songs in we all heard Gord sing, "lined with pictures of our parents' prime ministers" -- and for everyone there, we realized that our prime minister, the man who leads us, the most important political entity in the Canadian government--

His father is on that metaphorical wall, and he, right now, is sitting with the rest of us, another fan in the stands, to pay tribute to the only storyteller that could possibly tell the story of how our culture was also his.

Justin Trudeau and his wife gave Gord a standing ovation. Hand over his heart, he saluted Gord Downie like our parents worshipped his father, and in so doing endeared himself to people like me even more. Because a man who can connect with the spirit and myth in the house of the Hip makes us feel like we voted in someone real. Not just a shell.

It's unthinkable to picture Harper, or even Obama, at a concert in a tee he'd bought at a merch stand. Harper worships at the altar of Alberta: progress, et cetera. Obama feels too larger than life to ever get to sit with the rest of us, really.

But Justin Trudeau saluted the Tragically Hip as if he had nothing to prove, nothing to gain except what I did, what everyone who proved the statement "Canada is closed -- #thehipinkingston" had to gain, all one million and more: to be a part of the culture we barely belong to.

He only wanted to be Canadian, too.

originally saved from cbc

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who said he had been a fan since high school, was there, in a black Tragically Hip T-shirt. "This is a moment that's going to be extremely powerful for all Canadians, I know," he said in a live interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation before the show. "Gord and the Tragically Hip are an inevitable and essential part of what we are and who we are as a country. And tonight we get to say thanks, and we get to celebrate that." --Melena Ryzik

I grew up in the Hip generation. Maybe that's obvious.

Here's something else I did, while listening to their obscurity: I grew up on the internet. By grade nine I owned "Day for Night", "Road Apples" and "Trouble at the Henhouse", and I was posting on message boards and, and, and.

These days, the internet isn't obscurity, it isn't anonymity, it isn't coasting down a gravel road in the dark with a stranger, thrilling but safe because no one knows you're there. Not anymore.

These days, you can't help but notice if you're a woman and on the internet: there's a lot people who really don't want you to talk.

Posting anything -- even something as non-controversial and completely Canadian as a personal article on the Hip -- is risky. Moreover, it seems reckless to put myself out there, a potential target for abuse. Toxic masculinity, thy name is the internet, more so than when I was that child who grew up on message boards.

Back then, the rule was, "don't give them your personal information, never tell anyone your real name, don't post pictures of yourself. Don't let the predators find out who you really are."

And yet, even with all the stranger-danger fear that came from AOL and CompuServe in 1994, it felt safer than it does now. Maybe because for the vulnerable, including women, back then our identities were hidden.

There's a lot that other people have said about toxic masculinity spilling over into the political sphere, how it's driving the current election cycle. Nothing demonstrates how dangerous it is to be a woman better than the attacks on Clinton. I wonder, sometimes, what it would be like right now if Justin Trudeau hadn't been elected, if Harper had stayed in power. What that kind of toxicity would feel like, north of the border.

'Canadian Twitter' -- if there is such a thing -- blew up the day of the Hip show in Kingston. Nothing explains how excited, and positive, the internet was better than Chris Hadfield retweeting the official Toronto Police feed saying, "Canada will be closed at 8:30pm EST August 20, 2016. Thank you and have a Tragically Hip day."

All the headbanging, molson and labatt fifty drinking dudes I had to duck away from at shows in my youth -- and oh, how -- they all took to the internet in order to air their grief; and grief unfettered by the repression that usually says, "men can't feel."

After the show, I saw one of the most heartening, the most touching photos: Justin Trudeau and Gord Downie, refusing to be cowed by the idea that men cannot be affectionate, cannot show love between one another, were snapped embracing, hands and arms and hearts open wide.

It was another demonstration of how generous, how open -- and yes, how feminist -- this tour has been. From Gord calling out women (on national television!), thanking them for coming back to their shows, to songs on their first few albums about scorned women, battered women, standing up and taking control, the Hip has shown themselves to support women. Even when their fans weren't as open.

Imagine it: August 20th, 2016, the two most influential men in Canada showed the rest of Canadian men that it was okay to really touch each other, and posted that courage on Twitter of all places -- a bastion of toxicity. One article, written by a woman who went to That Night In Toronto, told an anecdote about a larger, drunk "hockey bro" turning to her and her boyfriend and asking, "Can I have a hug?"

But he wasn't asking her; he wanted to embrace her boyfriend. Where else, when else -- who else could bring men to their emotions more readily?

The Hip are a generous, and genuine band; I don't think anyone would argue that. They're also a band that has -- through example -- shown men how to be the same.

canada's version of the wave, kingston hip show, august 20, 2016

"If our favourite band leaves us confident in only one thing, it's that what makes us Canadian is not simply our un-Americanness." --Mia Pearson

One of the things that people have been trying to write about ever since this tour started -- ever since this tour was announced -- is how Canadian the Hip are.

Gordie Downie is the unofficial poet laureate for Canada, according to the CBC -- and if anyone was in a position to name someone thus, it's the CBC. The Hip are "the quintessential Canadian band", providing the Canadian identity we didn't know is missing. Part of that is, if you attended high school in Canada in the 1990s you couldn't avoid the Hip, not anywhere FM top-forties radio ruled (middle class white Canada, but other places too). All of this has been said -- "they told Canadian stories" is the truth, name-dropped small Ontario towns with small Ontario characters. They talked about hockey as if they sat watching it.

Making fun of the Leafs is practically an Olympic sport, but god help anyone else who does it.

(To clarify: hockey died to me in 1994 when the Canucks failed to win the Cup in sudden-death overtime, game seven. The answering call from the city of Vancouver? Riots. A country that's known for too many apologies set its most beautiful downtown core on fire when the NY Rangers won.)

This dichotomy, however, is what makes the Hip Canadian. A few articles I read touched on this: The Hip talk about the messy side, the underside, of our Canadian pride. Molson's commercials proclaim, "I Am Canadian", but fail to acknowledge that almost 40% of Canadians have parents who were born elsewhere, fail to show indigenous treaty failures and the country's indifference to indigenous rights.

Gordie Downie took a live CBC broadcast and called out the entire country, took it to task for that indifference, called us out for ignoring indigenous communities. "Canadian culture", whatever that means, has its share of issues, and throughout their long tenure, the Hip have narrated them all.

The second-ever Hip show I managed to see was in Toronto on Canada Day. How apropros: hockey bros, beer, barbecues, and fireworks.

I saw the Kingston show from the back of the arena. I saw all the crowd, all the heads, all the hearts as a huge wave of people, dots in turn. I couldn't see the band, not really. The Edmonton show I watched was the opposite. Our seats were so close I could see the tears on Gord's face as he turned away from the audience.

These two views provided equally rewarding experiences; showcased the Hip in two different ways, just like they showcase ourselves back to us. If Gord Downie is the Canadian poet, then he mirrors our own crowds and our own tears.

The Canada Day show I went to was in a sunny park, in north Toronto, in a neighbourhood known for low-income housing and non-white families. The park itself is considered positive part neighbourhood planning, ignoring it isn't accessible for those in the surrounding housing; a perfect example of smug Canadianism, that fails to see where we could do better. I honestly can't remember if The Hip called us on it: drinking our beer while the apartment towers a few kilometres away have trouble affording basic necessities. But I would think they probably did.

The Hip don't let us gloss over the things about being Canadian we want to forget.

I know we couldn't see the stage from where we lounged in the grass, drinking overpriced beers and feeling good about our passports. We should have listened closer, I guess.

What The Hip really offer us is a chance to both be a close-up viewer of the good and bad of the great white north, as well as a birds' eye view. All these messy pieces are part of Canada, et cetera. They'll do the music, and we need to fix the details.

my own little hipstamatic print

"�Fiddler's Green� is one boy I loved, �Wheat Kings� is all the others." --Jen Selk

So how did I get into the Tragically Hip? What was the first song I fell for?

I wish I could say it was something edgy, like "Fifty Mission Cap" or "Terrarium", but it wasn't (though I do have a huge fondness for the latter). I wish I could say I loved "Last American Exit" first, but I was too young.

At the Edmonton show, The Hip did end up playing the first song from their catalogue I ever fell in love with, even though the day before I'd made a bet they never would. "Scared" maybe isn't their most loved or best known song, but when it was released, it was a well-known single. I know that, because it got played on the radio. It was played on the radio to death.

I know that, because that's how I fell for it: listening to the radio and then, listening to the cd on repeat, learning all the words.

At the time I was an awkward, confused high school kid. I don't think I really had any idea what the song was even about, what it meant -- not that The Hip are ever overt in meaning. I remember loving the line "can I get out of this thing with me an' you", and the melody, and Gord's voice. I guess -- no, I know -- that was enough.

After the Edmonton show, but before the Kingston show, a lot of us started reading all the news coverage of The Hip's tour. People's retrospectives, thoughts, feelings -- Canada's grief, fresh on the page. We had to share in it, had to experience it, to really feel whole.

One of my favourite lines was from a Buzzfeed piece, about the first boy you loved, and all the others. At the time, I thought of "Scared" -- how many times have we asked to get out of that thing with me and you? Too many times. Oh, too many times. The first boy who breaks your heart, that painful cleave, that bittersweet acoustic melody does fit, doesn't it?

But as true as that is, it wasn't until I read the possible happily ever after of "Emperor Penguin" -- different writer, same Buzzfeed post -- that I was reminded of a long-buried dream: "the choice to keep going together is love." I never though "Emperor Penguin" told that story; all I heard, at the time, was "the kiss that's still intangible" and assumed nothing would last.

By the time Phantom Power came out I was in grade 12; by the time it was popular I'm pretty sure I'd already fallen for another boy who'd break my heart. We first bonded over Canadian remixes, one night in Toronto, over our love of The Hip and Big Shiny Tunes and beer, and I was probably half-way there.

I wouldn't admit it for another five years.

High school was "Day for Night" and "Trouble at the Henhouse" and "Phantom Power". All those songs, all those lives. "Phantom Power" came out the same year I met the first boy who broke my heart, but "Emperor Penguin" wasn't his anthem. Gord was too obscure, too ambiguous, for the deep ache he left behind.

But in hindsight, that's perfect, because he was always obscure, never clear.

Maybe Emperor Penguin was the first boy I loved, and Wheat Kings all you others.

my own print

"What if he murders me, I wondered as I clambered into the car next to him. Maybe this is how I will die. At the hands of a strange boy in a car. I didn't die, but I did fall in love for the first time." -- Erica Ruth Kelly

So as you might have already guessed, when I was sixteen, I fell for this kid I knew. Hard.

He was everything that you want when you're kind of messed up and sixteen -- sensitive and aloof, more hip than me, and god, more messed up than I was. He introduced me to nearly all of the bands I've had life-long love affairs with: Radiohead, Beck. 54-40. Half of the 1990s rock and alternative that was my high school soundtrack -- and everyone else's, too -- started with him. The entire genre of music that's been My Jam, that was all him.

In fact, almost all the bands I love, someone else introduced me to, so when I listen to them, I can't avoid that fact, I can't avoid that someone else's DNA is written into the song.

So here's a surprise: I found the Hip on my own, listening to FM radio in my room, alone and waiting for life to start. The first album I fell for was "Day For Night", as I said, the song was "Scared". I don't know what spoke to that thirteen year old back then, I don't know why I loved it, only that I did. The Hip weren't my first CD, but they were one of the first five.

To make a long story short, the kid I fell for at sixteen did a number on me in the way that only sixteen-year-olds can do; to make a long story shorter, he disappeared without a trace. In my head, it was Romeo and Juliet, if Romeo ran from Verona without a forwarding address. To him, it was little.

I haven't known if he was even still alive for nearly twenty years.

The day before I got on a train to Kingston to see the Hip (for the last time...for the last time? Maybe for the last time), I went out for drinks with some friends, who introduced me to a man who could have been Romeo's brother, if that kid had grown up strong, had cleaned up, if I met him in a bar in Toronto's west end. This man's name is Walter, and watching him that night was like looking at a ghost. The Ghost of Happiness Maybe Yet to Come.

Romeo didn't give me The Hip, but that doesn't mean I don't think about him when I listen to them. After all, on an album that has "An Inch An Hour", "Grace Too", and "Nautical Disaster", I wept at "can I get outta this thing with me and you".

The night before the Kingston show was like a time warp, transporting me into a time and place a decade before; when listening to the Hip in That Bar, on That Street, was commonplace. Natural.

Not a big deal.

If I'd met Walter when I still lived there, maybe it wouldn't have been such a shock to the system, such a jolt of terrifying memory. Maybe I would have gotten to know him like I did Ryan and all the rest, and it would have been the same kind of nostalgia as listening to Nautical Disaster: gentle, misty. Blurred, like the rest of my memories. But because I didn't get the chance to settle in, meeting Walter was being plunged into icy waters, no chance to recuperate or get used to the blow. You know?

Everything about Romeo was both obscure and a shock -- even the connection between him and the date at the start of this part, even the song I really think of when I think of him. The funny part is, I'm still not sure I know Romeo's real name.

my own print

"If the Hip are a complicated series of pulleys and ropes, maybe a lift lock, or an old Ontario mill, I was once entangled in them, having skijored across Canada in the 1990s opening for the band." -- Dave Bidini

So I've been telling everyone since this tour started that it only makes sense I try and go to see it; for years and years I've been a Hip fan, one of the only bands I came to on my own terms, without someone else having said, "listen, listen to this one!"

Not only that, but I've only had the chance to see them twice before in my entire life -- either too poor or too snobbish to pay the outrageous stadium prices that would follow their tours.

So I've been telling everyone, "listen, it's fate: the first time I saw them was 1996, and then 2006. So 2016, of course, of course that's next."

The way we rewrite our memories to make them more narratively driven, the way we manage to tell ourselves the stories that make up our life, it's a fascinating process. Not content to say, "I've only seen them twice; please, please let me get the chance once more," I had to space it every ten years.

Here's the thing that I didn't realize until I started writing this: neither of those dates were correct. Google tells me I saw them July 1st in 2011, and that Another Roadside Attraction wasn't 1996. My memory is muddy enough to tell the story I wanted, not the truth.

What I remember is this: I had a ticket to Another Roadside Attraction. It wasn't the first concert I ever went to in my life, but the second. It was the first I went to without an adult. Me and a friend of mine got in my aunt's car, she dropped us off near the bus route into UBC, and clutching our tickets, we stumbled through this confusing world, following the rest of the crowd to Thunderbird Stadium.

I was fourteen at the time. I'm fairly certain my mother didn't know my aunt hadn't come.

So we get inside the stadium -- for those of you who've never been inside Thunderbird Stadium at UBC, it's a truly terrible concert venue. The acoustics are awful, there's nowhere that you get a decent view, and it's usually full of drunk bros (this is UBC).

We didn't care. We saw the show.

Here's the part that, if I were telling a story, I wouldn't admit to: I can't remember the set. I don't remember if we got there in time to see Rheostatics, or Spirit of the West. I can't remember any of the songs they played. I don't remember my first Hip concert.

I do remember being bewildered and a little afraid, surging out of the stadium after the show -- still following the crowds to exit as if they knew where they were going -- to meet up with the aunt that was driving us back home. This was a time before cel phones. We were soaked, and cold, and excited, Jennie and I, feeling grown up and hip. "Look at us, we're at a concert by ourselves."

Look at me. I can tell a story of seeing Rheostatics and Spirit of the West open for the Hip, before it was cool.

Look at me, I can tell the story of being at the Kingston show, August 20, 2016. I wept when Gord told us it was a pleasure. I will always know I wept, then, but I'll never know how I felt hearing "Scared" live in high school.

That set list isn't even available online, lost to the winds. I love the openers, but Google is the only reason I know the Rheostatics were there.

Here's the thing about using your memories to retell the story of your life: the details fade into obscurity, they stop being as important. Here's the other thing I shouldn't admit to: the first show I went to wasn't 1996.

On July 13, 1995, I saw my first Hip concert. I know this not because I remember it, not because I still have the ticket stub (it's pasted into a journal I gave away years ago, if anywhere). I know it because I found a review of the show online, which told me the date.

My memory is certainly muddy, but maybe the date, the details, don't matter anymore. I know I was excited. I remember the bus ride back to the parking lot to meet my aunt. I remember Jennie and I looking around, wide-eyed, a whole new world opening up: shows. Concerts. Venues full of people singing along, rowdy and imperfect.

So I went to Another Roadside Attraction in 1995. I was in grade nine. On August 20, 2016 -- twenty one years later -- I went to Man Machine Poem. And so did everyone else.

Maybe that's enough.

As dark rings the door

With body to take,

You are the ocean, and

I am just a lake.